While undertaking year-end tax planning, one cannot ignore the various pushes and pulls to a taxpayer’s global effective tax rate (ETR) that have arisen within the last year or so. Taxes and trade have noticeably stepped into the foreground of the geopolitical environment. Globally, many countries have or are implementing Pillar Two minimum taxes and digital services taxes on large multinational enterprises. Domestically, the Trump administration passed sweeping tax reform enacting this term’s flagstone piece of legislation, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (the Act) (P.L. 119-21) while also attempting to balance the scale of taxes and trade by leveraging tariffs, customs duties and certain retaliatory income tax provisions in negotiations with our trading partners. Large multinational enterprises operating from or within the United States should understand and model out these and other U.S. tax law changes, which, if gone unchecked, could have surprising implications.

To assist in planning for the year ahead, this update highlights key changes made by the Act that are significant to U.S. international tax law (building upon earlier and more detailed releases on point as further referenced below) as well as previews other relevant guidance updates made via notice or regulations. Lastly, this insight provides a high-level update on the state of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Pillar Two rules (previewed here) and insight on how U.S. policy, law changes and ongoing negotiations may play a role in its calculation and/or its overall future state.

As prefaced earlier, the Act integrates numerous fundamental changes significant to U.S. international tax law including those impacting each of the following:

- The global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) regime,

- The controlled foreign corporation (CFC) pro rata share rules,

- The CFC tax year conformity rules,

- The rules that determine CFC status with the reinstatement of section 958(b)(4),

- The foreign derived intangible income (FDII) deduction,

- The base erosion and anti-abuse tax (BEAT), and

- The foreign tax credit (FTC) limitation.

In addition to the welcome reinstatement of section 958(b)(4) in proscribing downward attribution from a foreign person in determining U.S. shareholder and CFC status as the normal operative rule, the Act introduces a new provision, section 951B, which codifies a new class of U.S. shareholders and CFCs: foreign controlled U.S. shareholders and foreign controlled CFCs necessitating a fresh look at legal entity organizational structures in reassessment of international tax reporting, obligations and implications resulting from these changes. Further, the enhanced deductions provided under the Act for business interest expense, bonus depreciation and immediate expensing of domestic research expenditures presents an interesting interplay with other potentially applicable provisions (e.g., GILTI, FDII, BEAT, corporate alternative minimum tax (CAMT) and Pillar Two) necessitating careful modeling to ameliorate any counterintuitive costs that might otherwise result from “too much of a good thing.”

An earlier release entitled the Revamp and rebrand of the GILTI regime in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act included a comprehensive list of changes that impact GILTI in a more direct sense (i.e., the removal of the substance based exclusion, the decreased net CFC tested income (NCTI) deduction to 40%, the increased allowable NCTI FTC of 90%, and the simplified expense allocation and apportionment for purposes of the NCTI FTC) as well as other changes that impact GILTI indirectly or proximately (i.e., changes to the business interest expense deduction limitation, the reinstatement of a proscription on downward attribution from a foreign person under section 958(b)(4), the removal of the section 898 one-month deferral exception, updated NCTI pro rata share rules and the permanent extension of the CFC look-thru exception). The earlier release discusses each of these changes in more detail, including the rebranding of GILTI as NCTI post-2025, planning considerations and effective dates.

It is generally anticipated that more taxpayers will be subject to GILTI on an NCTI basis due to the removal of the qualified business asset investment (QBAI) exclusion. Since the requirement to allocate and apportion U.S. interest and research and development (R&D) expenses has statutorily been eliminated, and the NCTI FTC haircut reduced to 10%, it is also anticipated that taxpayers may see an increase in foreign tax creditability in ameliorating the effect of double taxation on such income. Considering these changes together with the NCTI deduction, NCTI transitions to be more in line with the general notion of a minimum tax at a rate of 14%. While all changes to the NCTI regime are objectively unfavorable or favorable, the effect of all collective changes will be subjective to each taxpayer in considering their particular facts and circumstances. For example, a taxpayer wholly owning a CFC operating in a low-taxed jurisdiction with substantial fixed assets on the books may have avoided any residual U.S. tax on a GILTI basis (0% top-up tax), however, post-2025 may be subject to residual U.S. top-up tax up to a marginal rate of 12.6% (without associated FTC claim) to 14% (with FTC claim) on an NCTI basis in the absence of the QBAI exclusion. A similarly situated taxpayer without QBAI could experience a more modest marginal rate increase of only 0.875% to 2.6% on an NCTI basis relative to a marginal rate of 10.5% to 13.125% on a historical GILTI basis. This assumes in both cases that the taxpayer can fully utilize any NCTI deduction and FTC. It is important that each taxpayer model the changes accordingly for ETR and cash tax planning purposes.

While the changes to GILTI do not take effect until taxable years beginning after Dec. 31, 2025, there are some items under the Act that are applicable earlier that may impact upon GILTI calculations. First, the reversion to an earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) basis for purposes of the business interest expense deduction limitation applies to taxable years beginning after Dec. 31, 2024. This change may lend itself to greater interest deductibility at the CFC level (and anecdotally coupled with other Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) provisions yet unchanged for calendar year filers in 2025) may provide a benefit to taxpayers in reducing any residual GILTI tax. Second, taxpayers utilizing the one-month deferral exception under section 898 will need to transition applicable CFCs to their taxable year beginning with the next taxable year of their applicable CFCs beginning after Nov. 30, 2025. Impacted calendar year taxpayers will then need to file two Forms 5471 for the 2025 calendar year (i.e., Jan. 1, 2025 – Nov. 30, 2025, and Dec. 1, 2025 – Dec. 31, 2025). Lastly, those taxpayers undergoing mergers & acquisitions (M&A) activity involving CFCs after June 28, 2025, should note that acquiring U.S. shareholders cannot reduce their pro rata share of GILTI for dividend(s) (actual or deemed) to the previous U.S. shareholders if such previous shareholders did not include such dividend(s) in income, and, furthermore, disposing U.S. shareholders might be on the hook for a pro rata share of deemed inclusion income post-2025 that more generally had previously been attributed that income only to the U.S. shareholder of record on the last day of the CFC taxable year.

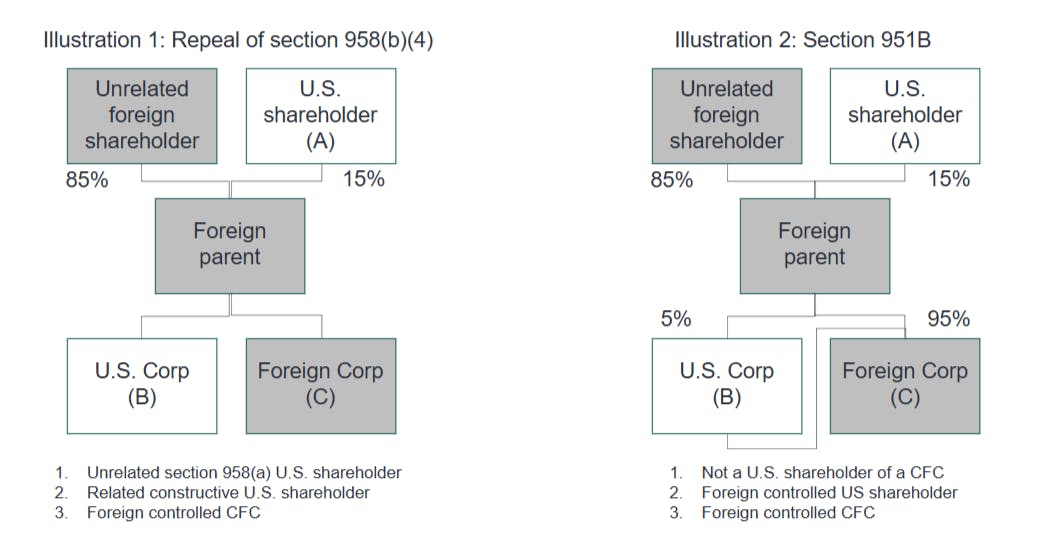

Taxpayers that were previously treated as U.S. shareholders because of the earlier repeal of section 958(b)(4) that prevented the constructive ownership of foreign stock through downward attribution from a foreign person (see (A) in illustration 1 below) will be finding relief from receiving deemed inclusions of income and filing Form 5471. Under new section 951B, only a foreign controlled U.S. shareholder who directly holds stock of a foreign controlled CFC will be considered to constructively own the remainder of such stock because of downward attribution from a foreign person. In this case, only the foreign controlled U.S. shareholder will be subject to deemed inclusions of income and filing requirements with respect to that ownership. These changes will apply to taxable years beginning after Dec. 31, 2025, so relief for existing unrelated section 958(a) U.S. shareholders is not available for the 2025 taxable year.

Lastly, by way of a technical correction, the Act clarified taxpayers do not need to gross up taxes deemed paid on distributions of previously taxed earnings and profits (PTEP) applicable to taxable years beginning after Dec. 31, 2025.

Another previous release entitled Revamp and rebrand of the FDII regime introduced four key changes to the FDII deduction, planning considerations and effective dates. The changes to the FDII regime include the removal of the substance-based (QBAI) hurdle, the simplification of expense apportionment to foreign derived deduction eligible income that removes the requirement to allocate and apportion U.S. interest and R&D expenses to foreign derived deduction eligible income (FDDEI), the decreased FDII deduction percentage to 33.34% and the exclusion from FDDEI of income from the sale of or disposition of intangible property or property that is depreciable, amortizable or depletable. Similar to GILTI, FDII is rebranded (here, as FDDEI) post-2025 with the removal of the QBAI hurdle.

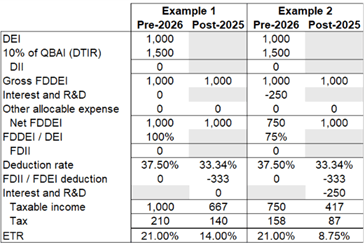

While generally the effective tax rate on qualifying export income increases from 13.125% under current law to 14% post-2025, because of the removal of the QBAI hurdle many more C corporations, particularly those with substantial qualified business assets, are expected to benefit from the deduction, or increase their existing deduction, on a FDDEI basis (see Example 1 in the table below). Further, taxpayers will no longer be required to allocate and apportion expenses that are not “properly allocable” to FDDEI income, including domestic research and experimentation (R&E) expenditures and interest expense. As a result, interest expense and R&E are deducted at 21%, and, to the extent these expenses relate to FDDEI could have the effect of further reducing the ETR on qualifying foreign income below 14% and perhaps into the single-digits (see Example 2 in the table below).

Taxpayers may wish to strategize the placement of intangible property (IP) and align supply chains to take advantage of this lower ETR. However, those wishing to do so should proceed with caution, especially larger multinational corporations. The increased ability to deduct interest expense (and interest expense carryforwards) in the reversion back to an EBITDA based interest limitation, the immediate expensing of domestic research expenditures (and/or the acceleration of previously capitalized domestic research costs), the reinstatement of 100% bonus depreciation and the increased viability of the FDDEI deduction are on the surface very taxpayer favorable outcomes. However, depending on a taxpayer’s particular facts and circumstances, these favorable items could lend themselves to lower regular tax liabilities and effective tax rates, potentially triggering additional tax under BEAT, CAMT and even Pillar Two. While there is a credit against regular tax due for taxes paid under CAMT, because of the current ordering rules, it is possible that these credits go unused. No such future credit is available for taxes paid under BEAT, thereby resulting in, through enhanced deductibility of expenses under the Act, the potential for an effective conversion of timing differences into permanent items from an overall ETR creep perspective where those other minimum taxes are applicable.

While most of the changes that impact FDDEI are applicable to taxable years beginning after Dec. 31, 2025, the exclusion from FDDEI for income or gain from the sale of IP or other property of a depreciable or amortizable nature (including imputed royalty income under section 367(d)) is effective for transactions occurring after June 16, 2025. Royalty income will still be considered FDDEI on a go forward basis.

The Act, as passed, does not substantially change BEAT. Under current law, the BEAT rate is generally 10% with an 11% rate applying to certain banks and securities. The Act increases the BEAT rate to 10.5% (11.5% for certain banks and securities). Further, the Act permanently extends the current treatment of certain credits (e.g., the R&D credit) such that they will not reduce adjusted regular tax liability for purpose of calculating the base erosion minimum tax amount (BEMTA). These changes will be effective for taxable years beginning after Dec. 31, 2025.

Proposed section 899 (the so-called “revenge” tax) would have likely subjected many more U.S. corporations to a modified-BEAT to the extent owned directly or indirectly by persons tax resident or organized in so called “discriminating foreign countries” (generally inclusive of those countries with an enacted undertaxed profits rule (UTPR) under Pillar Two and/or an imposed digital services tax). In light of the G7 nations informally agreeing to a side-by-side solution that seeks to exempt U.S. parented multinational groups from Pillar Two minimum taxes being assessed under either an income inclusion rule (IIR) or a UTPR, this provision was pulled from the Act before passing. To date, no formal agreement has been made (including no formal changes adopted by the OECD in light of the earlier G7 agreement) and, as such, could lead to the reintroduction of the revenge tax in future legislation.

The TCJA modified how income from produced inventory property is sourced to be solely based on the place of production. This left certain U.S. manufacturers that facilitated global expansion via foreign sales offices exposed to double taxation as it limited their ability to take a foreign tax credit. The Act provides a solution for this class of taxpayers by allowing foreign source treatment for purposes of the FTC limitation but only to the extent the sales are attributable to a foreign branch office (or other fixed place of business) and for foreign use. The foreign source treatment is subject to a 50% limitation based on total taxable income from the sale or exchange of such inventory property. This change will be applicable to taxable years beginning after Dec. 31, 2025.

Also, post-2025, taxpayers are statutorily no longer required to allocate and apportion U.S. expense deductions, including those for interest and R&D, that are not directly allocable to NCTI for purposes of the FTC limitation. Any amount of expense that would have been allocated to the NCTI category prior to this change, will be allocated and apportioned to sources within the U.S. While this simplification is generally good news in terms of increasing the creditability of foreign taxes within the NCTI category (as well as within other section 904 limitation categories which do not absorb any reallocation of expense away from the NCTI category), taxpayers need to consider how this (in conjunction with potentially increased deductibility of U.S. interest and R&D resulting from the Act) could implicate application for the overall domestic loss (ODL) rules. Lastly, critical guidance is still forthcoming from the IRS and Treasury that will prescribe the appropriate method of allocating deemed foreign taxes paid to the NCTI category on a fixed and determinable basis with respect to the loss of the one-month deferral election under section 898.

On Dec. 10, 2024, nearly 40 years after the enactment of section 987, final regulations were issued addressing various aspects of foreign currency translation with respect to certain qualified business units (QBUs), including determining taxable income of, and gain or loss on remittances from, such QBUs. Generally, the final regulations apply to individuals (except for nonresident aliens) and corporations (including CFCs where there is a section 958(a) U.S. shareholder) that own section 987 QBUs. Section 987 QBUs are QBUs with a non-hyperinflationary functional currency which is different than that of its tax owner.

Taxpayers that are within the scope of the final regulations will need to determine how to appropriately transition to the final regulations. This is dependent on the method, if any, previously adopted by the taxpayer. Taxpayers that had not previously adopted a foreign exchange exposure pool (FEEP) method prescribed by earlier proposed regulations must determine if the method currently applied is an “eligible pretransition method” or an ineligible method. If utilizing an eligible method, the taxpayer can apply that method to calculate its pretransition gain or loss as of the day before the transition date (Dec. 31, 2024, for calendar year taxpayers). If using an ineligible method (or no method), the taxpayer must calculate their pretransition gain or loss using a modified FEEP method for a limited look-back period (taxable years beginning after Sept. 7, 2006) as prescribed by the final regulations. While pretransition gains are considered unrecognized section 987 gain, pretransition losses generally are suspended until a later year only to be used to the extent section 987 gain is recognized within the same recognition grouping (the loss-to-the-extent-of-gain rule). Pretransition losses will not be suspended if a current rate election is made for the year beginning on the transition date or if the taxpayer makes an amortization election to recognize pretransition gain or loss ratably over a ten-year period. Taxpayers should be aware that transition information will need to be reported on tax returns filed for the taxable year beginning on or after the transition date (taxable years ending Dec. 31, 2025, for calendar year taxpayers). In-scope taxpayers should consider calculating pretransition gains and losses soon, if they have not done so already. Further, taxpayers should consider the impact of any pretransition gains or losses (particularly suspended losses) for year-end financial statement reporting.

Post-transition, in-scope taxpayers will need to continue to track annual unrecognized section 987 gain or loss using the ten-step FEEP method prescribed by the final regulations. Taxpayers may choose to apply the current rate election or the annual recognition election. The current rate election removes the complexity of having to translate historic balance sheet items at historic exchange rates, which, coupled with an alternative calculation of QBU net value, eliminates the need to maintain tax basis balance sheets for QBUs. However, if a recognition event (i.e., a remittance or termination of a QBU) occurs while the current rate election is in effect, any resulting section 987 loss will be subject to the loss suspension rules. The annual recognition election mitigates the effect of the loss suspension rules by requiring the annual recognition of any unrecognized section 987 gain or loss (regardless of a recognition event occurring). Taxpayers can also choose to make both the current rate and annual recognition elections, however, these elections cannot be revoked for a 60-month period and, thus, require careful consideration and modeling.

Partnerships and S corporations, while more broadly excluded from the scope of the final regulations, must still comply with section 987 in a manner consistent with statute. The final regulations will apply to partnerships and S corporations with respect to the rules governing the character and source of section 987 gain or loss, suspended losses, deferral of section 987 gains or losses, the annual rate election and the section 988 mark-to-market election. Note that partnerships and S corporations are not subject to the transition rules, however, it is anticipated that eligible pretransition methods described therein would be considered reasonable methods of applying section 987 with respect to these entities. Further, the final regulations do not dictate how section 987 will be applied to partnerships and S corporations (i.e., under an aggregate, entity or hybrid approach) and taxpayers can choose one of these approaches subject to a consistency requirement.

While the first Trump administration had pulled an earlier version of the section 987 regulations, currently, it is not expected that the final section 987 regulations will be pulled by the current administration, so taxpayers should be prepared to comply with their requirements.

Other recent and notable regulatory and additional administrative guidance updates are as follows:

- In September 2024, proposed CAMT regulations were issued that expanded the scope of the term foreign corporation with respect to the common parent of a foreign parented multinational group (FPMG) to include a “deemed foreign corporation” that would treat certain foreign partnerships as foreign corporations for the purposes of the FPMG adjusted financial statement income (AFSI) test. It is expected that these regulations will be revised and/or potentially (in whole or part) be withdrawn under the current Trump administration.

- Final section 367(d) regulations were issued in October 2024 that relieves deemed inclusions of income from earlier outbound transfers of IP upon the subsequent repatriation (or domestication) of that IP to the extent the recipient is a “qualified domestic person”. This is welcome relief for taxpayers looking to remediate prior inadvertent outbound transfers of IP, and, for those having intended prior outbound transfers, potentially beneficial if looking to now repatriate that IP as part of its overall IP situs/value chain alignment planning efforts.

- Proposed PTEP regulations were issued in November 2024, which would implement concepts introduced by Notice 2019-01 as well as describe how to properly account for corporate and shareholder-level PTEP accounts, dollar basis pools and PTEP tax pools. Early adoption of the regulations is available to open years once finalized, however, it is expected these regulations will be revised and/or potentially (in whole or part) be withdrawn under the current Trump administration.

- Final regulations were published in January 2025 that provided guidance on the classification and sourcing of digital content and cloud transactions. On this same date, proposed regulations were issued that would expand on the sourcing rules specific to cloud transactions. It is expected that these proposed regulations will be withdrawn based upon public comments from officials at the IRS and Treasury.

- Final dual consolidated loss (DCL) regulations were issued in January 2025, which only finalized a component of the earlier proposed regulations that were issued in August 2024 (i.e., the disregarded payment loss (DPL) rules). In August 2025, Notice 2025-44 announced the intent to issue proposed regulations that would withdraw the DPL rules. Final guidance on how the DCL rules will interact with Pillar Two is still forthcoming.

- Notice 2025-45 was released in August 2025 that provides relief in granting potential nonrecognition treatment for “covered inbound F reorganizations” from triggering the foreign investment in real property tax act (FIRPTA) rules.

- Final regulations were issued in April 2024 with respect to domestically controlled qualified investment entities (DC-QIEs) that finalized special look-through treatment for nonpublic domestic C corporations in application of the FIRPTA rules. In October 2025, proposed regulations were released substantially withdrawing the special look-through treatment with the IRS and Treasury largely agreeing with earlier taxpayer criticisms in this regard.

At a high-level, large multinational enterprises (MNEs) with consolidated financial statement revenue greater than €750 million in at least two of the last four fiscal years fall within the scope of Pillar Two. Pillar Two top-up tax is assessed via various charging provisions: the qualified domestic minimum top-up tax (QDMTT), the IIR and the UTPR, which collectively work together to ensure these organizations are being taxed at a rate of at least 15% in each country in which they operate. To date, many countries globally have implemented one or more of these charging provisions, which includes most of Europe. While the U.S. has not implemented Pillar Two, there remains an overarching concern that U.S. parented multinational groups will be subject to these extraterritorial top-up taxes on U.S. income through the application of a subsidiary jurisdictions’ UTPR as they come into effect starting in 2026 (once the UTPR safe harbor expires). A U.S. multinational group being subject to a UTPR could effectively neutralize the benefit of certain U.S. tax incentives that would otherwise reduce the U.S. tax liability and ETR (e.g., R&D credits and the FDII (or FDDEI) deduction).

As noted earlier, while U.S. legislators were in the midst of drafting the Act, which at that time included the revenge tax, G7 member countries reached an informal agreement that would exempt U.S. companies from tax under an IIR or a UTPR. This agreement being predicated on the notion that a “side-by-side” solution would recognize the U.S, tax system’s existing minimum tax regimes (i.e., GILTI, BEAT and CAMT). In exchange, the revenge tax was removed from the Act, which, in addition to modifying BEAT, would have increased income and withholding tax rates applied to residents of discriminating foreign countries. To date, there still has been no formal agreement, which opens the door for the potential reintroduction of the revenge tax.

Separately, while the NCTI ETR is generally 14% post-2025 (only a percentage point less than the 15% minimum tax rate under Pillar Two) and the CAMT rate is 15%, the ability of the FDDEI deduction to generate single digit ETR on qualifying foreign income (as illustrated in Example 2 earlier) in further driving down the overall U.S. ETR could inhibit the viability of any “side-by-side" solution. However, the example above is an extreme case, in which it assumes the sales are exclusively export sales, and, therefore, a single-digit ETR will be difficult to achieve for most U.S. taxpayers.